Land surveyors from the AGH UST, for 4 years, have worked together with archaeologists to document historical artefacts that were unearthed on the premises of a settlement which dates back about 2,000 years and is located on the premises of the Wda Landscape Park (Kujawsko-Pomorskie Province). During the conference and seminar that summarised the past investigations, some of the most interesting findings have been presented, including a unique pendant that came to northern Poland from the territory of today’s Ukraine.

In 2018, two archaeology doctoral students – Jerzy Czerniec from the Institute for History of Material Culture of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw (IAiE PAN) and Mateusz Sosnowski from the Nicolaus Copernicus University Institute of Archaeology in Toruń – found traces of a settlement in the Osie commune, on the premises of the Wda Landscape Park. The remains of the settlement have long evaded the perceptive eyes of modern researchers, since the 170-hectare area where it is located is covered by a lush forest. The scientists have made this discovery using data collected during ALS (Airborne Laser Scanning). When they were examining the digital terrain models available on the government website Geoportal.gov.pl, a completely preserved spatial layout emerged before their eyes, made up of enclosures, farmland, balks, and even roads. The nature of the discovery was truly unique on a European scale.

Archaeological work carried out on site has determined that the settlement was active between year 2 and 4 CE. ‘Archaeologists classify the remains as belonging to the Wielbark culture. However, the people who inhabited the settlement were probably Goths. They are peoples who came to our lands from Scandinavia about 1 CE. Until now, we had no idea from which region exactly. Some claimed that it was the Jutland Peninsula or Scania. Our research, however, has shown that those people might have come from today’s Norway because we have a number of artefacts that we can analogously link precisely to Western Scandinavia’, explains Mateusz Sosnowski, who combines his doctoral studies with work in the Wda Landscape Park.

Artefacts that speak volumes about the settlers

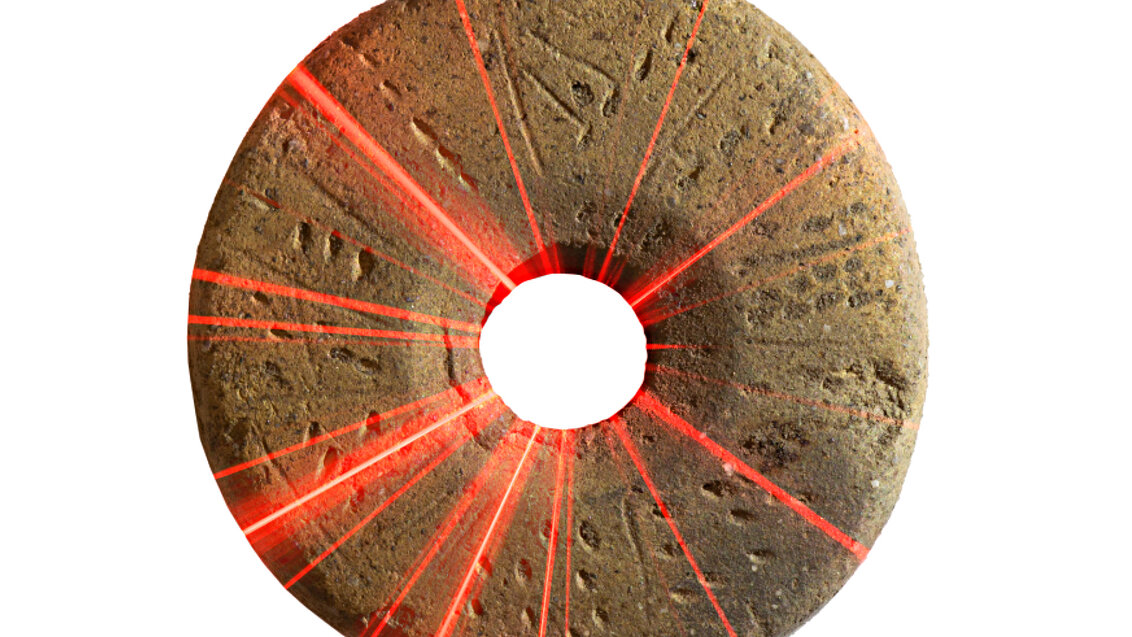

Archaeologists working at the site of the settlement have found objects characteristic of the northern parts of Europe, namely a weaving sword with a grindstone, a spindle whorl, and a langseax-type knife.

However, the past inhabitants did not only make contact with that part of the continent. The real archaeological sensation was brought about by last year’s studies. The archaeologists have discovered a round bronze pendant, with its circumference decorated with eight ducks. The scientists have found that it came from the territory of today’s Ukraine and that it can be linked to the so-called Chernyakhov culture which, similarly to the Wielbark culture, has been associated with Goths. As of now, only four objects of this type have been unearthed, none of them, however, preserved in its entirety. Here, the real treat is not only the fact that the piece is intact, but also that there is a link to a specific spatial context.

Other unearthed artefacts testify to the relationship of the settlers with the territory of the Roman Empire. The most valuable findings include a copper scallop-shaped piece from a horse harness used in the Roman army between 3 and 4 CE. It could have belonged to a mercenary or been a war trophy.

However, the settlers dabbled not only in warfare and farming – to which the aforementioned farmlands could point. ‘This was not a regular rural settlement where they focused only on agriculture. We know that there had been diverse crafts there. We are in possession of archaeological objects that can be directly linked to iron smelting and metallurgy, including various tools form making iron items. There is also ground for the hypothesis that the settlers produced ornaments and jewellery from bronze. Our investigations had led us to a place where we found a substantial accumulation of sinters that are incidental to the manufacturing of this metal’, the archaeologist says.

Data analysis algorithms

The academic employees of the AGH UST Faculty of Mining Surveying and Environmental Engineering, as well as students from the Student Research Club KNKG Geoinformatyka, have been working together with the archaeologists for four years. ‘It all started with a professional course, conducted at our faculty, related to Geographical Information Science (GIS), of which Jerzy Czerniec from IAiE PAN was a student’, Professor Krystian Kozioł recounts. ‘The course always responds to the current needs of the market, enjoys a good reputation among various professionals, and the final theses yield interesting projects. Sometimes, it lays the foundation for a broader cooperation’.

Land surveyors, archaeologists, and students participating in field work. Photo by Faculty of Mining Surveying and Environmental Engineering

A similar thing happened with the discovery in the Wda Landscape Park. When analysing digital terrain models, the archaeologists found regular structures that testify to previous human settlement in the area, but their picture was not yet complete. Only after Jerzy Czerniec and Professor Krystian Kozioł joined forces, and when the latter suggested using advanced algorithms for digital terrain model analysis, the cloud of seemingly unrelated points started to crystallise into objects that the archaeologists were after.

‘Archaeologists look for places that had been changed by humans by browsing the so-called “hillshades”, that is, numerical terrain models with realistic shading, available on the Geoportal. They don’t always reveal everything at first glance; therefore, we use a dozen or so analytical algorithms. One of the most interesting is the “open skyview factor” that shows everything that is around us in a given area from the point of view of an ant looking up at the sky. Obviously, this is not the 3D image that Google made us used to, but a purely mathematical distribution of changes in the intensity of gradients of the numerical terrain model, which allows us to see certain specific shapes’, Professor Kozioł describes.

‘Professor Kozioł was our mentor in geoinformatics. He guided us and recommended the algorithms which we used to obtain better images of the terrain under investigation. Our cooperation allowed us to determine the detailed boundaries of this site, which were subsequently confirmed administratively and entered to the register of heritage’, Mateusz Sosnowski states.

Digital twins of archaeological sites

AGH UST surveyors have also contributed significantly to excavation at the site of the settlement. Starting in 2019, they have participated in three such camps. Their primary tasks include establishing a geodetic network on site, a mesh of points with specified coordinates. Thanks to the network, when archaeologists find a particular historical object, they are able to precisely pinpoint its location. Additionally, by using the mesh, they are also able to interpret the spatial relationship between the findings.

The faculty employees also use their knowledge and expertise by taking stock of particular objects and excavation sites. ‘As part of archaeological documentation activities, we have performed measurements using terrestrial laser scanning and short-range photogrammetry. This occurred in two instances. The first one pertained to objects, for example, stone burial mounds visible in the terrain, and the geodetic measurements aim to catalogue them. Another situation in which our methods came in handy is the direct stocktaking of the progression of archaeological works. When the archaeologists dug a trial pit, its subsequent layers were scanned. This allowed us to speed up the work significantly, because normally archaeologists would have to sketch the excavation manually’, says Stanisław Szombara, DSc.

Paulina Lewińska, DSc, adds: ‘Each archaeological activity is defined as non-destructive. If an archaeologist excavates something and removes the cultural layer, they destroy it. We document things in 3 dimensions on the spot, something that no one will be able to recreate later. Due to the fact that we are using precise instruments, we are freeing ourselves from the mistakes that might occur during subjective interpretation of the sketcher’.

The so-called digital twin of one of the excavation sites. Materials from the Faculty of Mining Surveying and Environmental Engineering

In the future, the so-called digital twins, created using the measurements performed by the AGH UST land surveyors, might be useful not only to archaeologists. The scientists would like to cooperate with the Wda Landscape Park and the local government of the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Province to create digital representations of the documented objects and share them with everyone interested in the cultural heritage of this region.

Laboratory tests at the AGH UST

This is not the end. The technologies that our scientists use to document large objects, they would like to use them in the case of much smaller ones, which the archaeologists were able to unearth during excavation work. ‘This is not new technology, and we want to do it in a very simplified way. We want to create a possibility to catalogue items directly after they had been unearthed, before cleaning them, and before we lose the chance to see them in the form they were discovered. Before that happens, we have to start with lab tests’, Professor Krystian Kozioł reveals.

Pre-election meeting with a candidate for the position of rector

Pre-election meeting with a candidate for the position of rector  Agreement on cooperation with OPAL-RT

Agreement on cooperation with OPAL-RT  Krakow DIANA Accelerator consortium members with an agreement

Krakow DIANA Accelerator consortium members with an agreement  Meeting with the Consul General of Germany

Meeting with the Consul General of Germany  More Academic Sports Championships finals with medals for our students

More Academic Sports Championships finals with medals for our students  Launch of AGH University Student Construction Centre

Launch of AGH University Student Construction Centre  Bronze for our swimmers at Academic Championships

Bronze for our swimmers at Academic Championships  Smart mountains. AGH University scholar develops an intelligent mountain rescue aid system

Smart mountains. AGH University scholar develops an intelligent mountain rescue aid system