Lightfastness tests of dozens of the most famous works by Edvard Munch from the collection of Munch Museet in Oslo. Photo source: Tomasz Łojewski

What do The Scream by Edvard Munch, Mickiewicz’s letters, tapestries in the Wawel Castle, Gutenberg’s Bible from the 15th-century, Egyptian sarcophagi, Michelangelo’s sketches, the Constitution of 3rd May, and the oldest surviving wooden residential house have all in common? All of the pieces have been studied by a researcher from the AGH University of Krakow. Dr Tomasz Łojewski from the Faculty of Materials Science and Ceramics has studied the most valuable and unique works of art in the world with non-invasive methods.

The research performed by Dr Łojewski in Heritage Science Lab is supposed to answer questions such as how to protect the most valuable pieces from hundreds and even thousands years ago, how to properly store and exhibit the most unique creations of human hands, so that the time and light would not take away their charm and distinctiveness. As part of his work, Dr Łojewski is occupied with reading concealed content of manuscripts, paintings, and prints on a daily basis.

How to see the unseen?

To help art conservators and museum come various research methods. One of them is microfade testing (MFT) which allows for predicting light-induced changes and may provide results essential for creating a preventive conservation plan of an artwork.

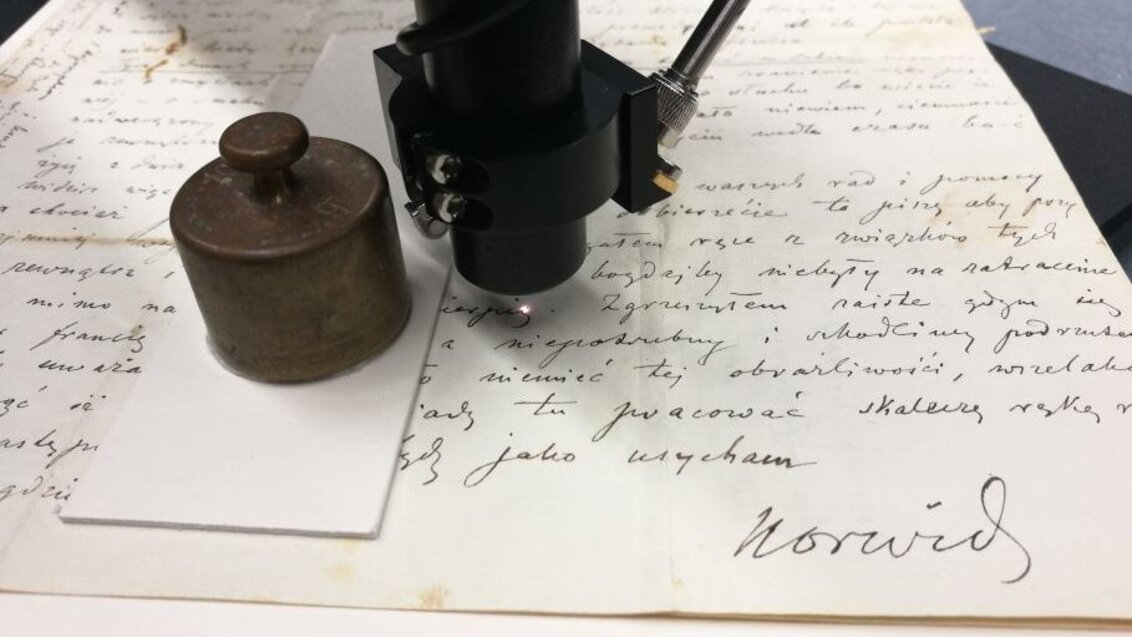

“Microfade testing is a relatively new method that makes it possible to determine the object’s vulnerability to light-fading in a non-damaging way. This technique may be used for all classes of materials found in museum collections. It is particularly useful for works made on paper, such as manuscripts, prints, watercolours, but also paintings and antique textiles. Microphedometry allows to considerably reduce the time of lightfastness tests from days to minutes and, moreover, it does not leave any traces of the tests performed,” explains Dr Łojewski.

Microphedometry is measuring the colour change during ageing tests when the object is exposed to a light source with a power of over 10 million lux [for comparison, in art galleries the lighting usually has 50-200 lux]. Owing to the measuring point having a diameter of only half a millimetre, the change of the colour taking place during the test is not visible to the human eye. As a result, this method is considered as non-damaging in the environment of art restorers, so it allows to study the originals, including those from the top tier of heritage treasures.

Microfade measurements allow to gain insight into how a given colour will change due to light exposure. Will the ink line fade and become illegible or will it darken and become more pronounced? Will today’s interference of an art restorer who replenishes defects in an oil painting or a fabric age quickly and become prominent against the original? Is the display on a gallery wall with the currently used lighting actually safe? Maybe the lighting conditions are too rigorous and the comfort of the visitors could be increased by brightening the gallery? Such questions bother museum professionals from all over the world and the demand for MFT is constantly growing. What is also increasing is the interest in the apparatus enabling the aforementioned tests, and the only producer of microphedometres is a Krakow-based company, Instytut Fotonowy. The instrument co-developed by Dr Łojewski is already used in 15 countries, in institutions such as the Library of the US Congress, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The British Museum, and, since last week, the Museum of Polish History.

Another method applied by the Heritage Science Lab is Multispectral Imaging (MSI).

“This is a technique in which, by the registration of numerous monochromatic images in a narrow range of waves and their statistical analysis, new, synthetic images in false colours are obtained, on which it is possible to notice elements invisible to the human eye and in a regular photography,” clarifies the researcher.

Analyses of oil paintings with the use of multispectral imaging technique. Photo source: Tomasz Łojewski

Researchers also use polynomial texture mapping (PTM), also known as Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), which is a technique of computer photography allowing to reveal elements of materials’ texture in a way that is not available in direct observation.

“When documenting pieces with the use of typical tools, a digital camera or a scanner, we register three-component images: red, green, blue. Layering them gives us an image in line with how we perceive the world with our eyes. Predominantly we are trichromatic – our colour vision is a result of the presence of three receptors in the retina, which register these three base colours. Human’s colour vision has a number of limitations – we cannot see infrared and ultraviolet radiation, our ability to distinguish shades of colours (about 1 million) cannot compare with that of birds or some insects (4 to 5 different colour receptors). The use of the right image capturing devices allows to overcome these human limitations and see more. Multispectral imaging serves precisely this purpose,” specifies Dr Łojewski.

The main scope of the application of multispectral imaging in the field of cultural heritage is making manuscripts, prints, maps, and drawings legible. The MSI sometimes allows also to detect repainting and preliminary drawings on painting works made in various techniques.

Could the king write?

Dr Tomasz Łojewski made studying relics of cultural entities in Poland and abroad his scientific specialty. The list of objects he has had the opportunity to analyse seems endless. Among the objects on paper (old prints, manuscripts, works of art on paper) and on parchment, historical fabrics, oil paintings, polychrome sculptures, numismatic items, ceramics from archaeological excavations, the following are certainly noteworthy:

- notes found on the walls of prison cells in Auschwitz-Birkenau and a notebook buried on the camp grounds belonging to a prisoner – member of Sonderkommando,

- Gutenberg’s Bible from the 15th century,

- Egyptian sarcophagi, dated between 8th and 10th century BC,

- letter of Amundsen to King Haakon VII, left on the south pole, testimony of early 20th-century explorer’s struggle for primacy,

- paintings by Edvard Munch, including a few versions of the famous “The Scream”,

- records of the Sejm session which make up the text of the Constitution of 3rd May,

- textures of wooden construction elements of a loft (Oslo) dated to the half of the 13th century, which makes it the oldest non-religious wooden building in the world,

- Rafael’s sketches and “Epiphany” by Michelangelo.

Letter by Cyprian Kamil Norwid. Photo source: Tomasz Łojewski

The common feature of all these items is the fact that their value for the culture and history is enormous, and they are sensitive to the destructive effect of the environment and may become unavailable to future generations. For scientists who support historians and restorers it is vital to understand the causes of degradation and find the best ways for their conservation, including preventive conservation, protecting from possible changes. One of the on-going projects are the MFT analyses in the Textile Conservation Studio at the Wawel Castle. Tapestries selected for the conservation process and analyses constitute precious works which got wet in transport boxes during the evacuation in 1939. The traces of that episode are visible until today, for example in the form of decolouring on some fragments.

“Within the framework of this project, we study tapestries in terms of their lightfastness, with the use of microphedometry, chemical composition, and microbiology, supported by scientists and researchers from the Faculty of Materials Science and Ceramics. The research and conservation works will continue until 2024. We aim to determine, for example, the vulnerability to light of the dyes of the threads used for restoring the tapestries."

An intriguing and at the same time invaluable document analysed by Dr Łojewski was also 16th-century Pacta conventa. This written obligation of the elected king included a number of promises, the failure to comply to which meant the loss of royal privileges.

“In 1573, Henry III signed a document brought to Paris from Poland, but the ink in which he dipped his pen faded and looks quite indistinctly today. As an alumnus of the Jagiellonian University, I was more than happy to undertake the task of making the King's signature legible, who promised, among other things, internationalisation of studies and funding for this very university.”

One of the most precious items studied by Dr Łojewski is the 15th-century Bible of Gutenberg. From almost 200 copies of the first book printed by John Gutenberg between 1452 and 1455 only 48 survived until today, with 20 complete ones. One of them, in a great shape, is in Pelplin, Poland, in the collection of Diocese Museum. The Gutenberg edition of the Bible has two volumes which are in Vulgate, the Latin translation. In the Pelplin (paper) copy the lettering is readable with very well preserved colourful initials. Leather binding and metal elements on both volumes are also in a good shape.

Determining lightfastness of selected elements of Gutenberg's Bible. Photo source: Tomasz Łojewski

“Our work was focused on examining and restoring this unique and highly valuable item. I had the pleasure to perform lightfastness tests of selected elements of the piece and take multispectral images of some carts. The good news is that low lightfastness is only displayed by the text lines, probably written with iron gall ink on the endpaper pasted against the cover of one of the volumes. Other tested writing, embellishments, print, and the paper itself show greater resistance to the damaging effects of light,” explains the AGH University scientist.

The results of analyses are used predominantly by museologists, among others during the preparation of plans for the protection of cultural heritage. However, multispectral imaging and polynomial texture mapping may be also applied in other disciplines. Forensics is a field in which these methods may be useful in reading content obliterated by atmospheric factors, people, or time. One of theses which are currently worked on at the AGH University under the supervision of Dr Łojewski concerns the application of the MSI in forensic analysis of modern-day inks. Additionally, the AGH University students have a possibility to learn about the examination of the works of art and landmarks during a selective course introducing into the topic but also to perform analysis of certain works themselves.More information on implemented projects is available on the website: home.agh.edu.pl/~lojewski.

Pre-election meeting with a candidate for the position of rector

Pre-election meeting with a candidate for the position of rector  Agreement on cooperation with OPAL-RT

Agreement on cooperation with OPAL-RT  Krakow DIANA Accelerator consortium members with an agreement

Krakow DIANA Accelerator consortium members with an agreement  Meeting with the Consul General of Germany

Meeting with the Consul General of Germany  More Academic Sports Championships finals with medals for our students

More Academic Sports Championships finals with medals for our students  Professor Jerzy Lis re-elected as AGH University Rector

Professor Jerzy Lis re-elected as AGH University Rector  Launch of AGH University Student Construction Centre

Launch of AGH University Student Construction Centre  Bronze for our swimmers at Academic Championships

Bronze for our swimmers at Academic Championships